“There are some churches which say ‘for us the cross is empty’ and I think they may be saying more than they mean to”

-Craig Keen

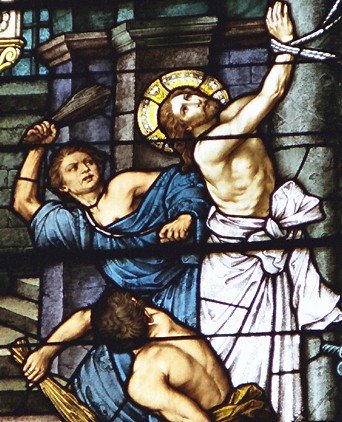

The torture of Jesus, as considered over the years, has become about as important to me as his death. Although placing Jesus’ death in the realm of abstract thought can be easy, the thought of torture could not be more concrete. How often do you think of the torture and death of Jesus as an injustice? Perhaps you are used to thinking of Jesus’ death as just “part of the plan.” The idea of Jesus dying for my sins works out well abstractly, but if you bring it back down to earth, you are saying that his death was not only divinely ordained, but that it was God’s plan for an innocent man to be whipped, beaten, mocked and executed by an oppressive power. We should see this as a terrible injustice which we can find and recognize in the surrounding world. Jesus being whipped and nailed to a cross becomes a symbol (though the word “symbol” is not nearly strong enough) of oppressed peoples all throughout the world and throughout history. Thus we cannot ignore “the least of these” any longer.

The torture of Jesus, as considered over the years, has become about as important to me as his death. Although placing Jesus’ death in the realm of abstract thought can be easy, the thought of torture could not be more concrete. How often do you think of the torture and death of Jesus as an injustice? Perhaps you are used to thinking of Jesus’ death as just “part of the plan.” The idea of Jesus dying for my sins works out well abstractly, but if you bring it back down to earth, you are saying that his death was not only divinely ordained, but that it was God’s plan for an innocent man to be whipped, beaten, mocked and executed by an oppressive power. We should see this as a terrible injustice which we can find and recognize in the surrounding world. Jesus being whipped and nailed to a cross becomes a symbol (though the word “symbol” is not nearly strong enough) of oppressed peoples all throughout the world and throughout history. Thus we cannot ignore “the least of these” any longer.

This is the incarnation: the violation of the rights of God and people, and the vindication of God and people over their oppressors through resurrection. If we are followers of Christ we must recognize this event and the events of oppression we see all around us, not as necessary for the greater good but as displays of evil to which there must be a response. The torture, death, and resurrection of Jesus carry huge implications for the salvation of the world. God responded to Jesus’ torture and death (though he didn’t stop it from happening) by vindicating him through resurrection. How will he respond to the torture and death of the oppressed? He does it by way of vindication. Yes, this should make the oppressor nervous.

Was the death of Jesus also about the forgiveness of sin? Jesus said it himself, that his shed blood was for the forgiveness of sin (Mat 26:28). On the cross (once again keeping incarnation in mind) Jesus forgives even those who oppress him. I cannot even express the power of those words, “forgive them, for they know not what they are doing.” Jesus ushers in a revolutionary response to oppression. It’s not violent revolution or systemic overthrow. It is forgiveness. God forgives the oppressor-all those working against him. But it is not the sort of forgiveness which gets us off the hook so we can simply live comfortable and ignorant lives. Our calling is to live lives of forgiven people-to live lives worthy of the gospel. Our calling is what Jesus said it was-“as the Father sent me, so I am sending you” (John 20:21). Our calling is to follow Jesus to torture, to death, and to resurrection. Our calling, as forgiven people, is to usher in a culture of forgiveness. Our call is to see Jesus in the oppressed-in the “least of these” (Matthew 25).

Filed under: atonement, christianity, Jesus, resurrection, the poor, theology, torture |

I know that you already know this, but I think we need to be careful how quickly we call the death of Jesus “easy.” The idea of God being dead for three days is by no means easy—even in abstract thought. I know you don’t mean to lessen the fact of his death, but I just wanted to point that out.

Danny,

Yes, you are certainly correct.

I believe you are referring to the sentence: “Although placing Jesus’ death in the realm of abstract thought can be easy, the thought of torture could not be more concrete.”

That sentence was not clear. What I meant by it is that it can be easy for us to reduce the death of Jesus to a theological abstraction, whereas torture brings Jesus suffering back into flesh-and-blood terms.

I agree, but feel it is important to delineate between the “nature of oppression in the crucifixion; that it, is was less political and more internally religious. Sure, Jesus lived in the midst of Roman imperialism, but the oppression so often spoke of in the gospels is that of a spiritual blindness–in which Jesus’ own people, the spiritual leaders, were blind to spiritual, not political salvation. Jesus makes little to no attempt speak out against Roman oppression. In fact he benevolently agrees to taxation (historically heavy taxation…heavier for those, like Jesus, who did not posses the coveted Roman citizenship) when he says, “give to Caesar what is Caesar’s, and to God what is God’s.” Jesus was not a political activist, and the torture he suffered under Roman rule was at the request of the subjects of his Judaic reformation.

At least that’s my opinion, which could very well be wrong.

nate,

crucifixion, however you paint it, was an example to whoever was watching of what happens when someone crosses Rome.

I appreciate your comment and you are right that there was a very deep spiritual element to what was happening on the cross. But I would argue that it is wrong to think that Jesus’ teachings would have been understood as politically neutral. Take the so-called beatitudes, for example, it’s quite a statement to say “blessed are those who are persecuted.” This would have been read as a slap in the face to Roman persecutors.

I acknowledge that the Gospels are trying to emphasize the Jewish rejection of Jesus (this is probably because by the time they were being written the Christian faith was being formed as distinct from Judaism for the first time in history) so they steer clear of putting direct blame on Rome. But, may I suggest, Roman condemnation would have already been assumed by the reader thus more convincing was necessary in the other direction, forcing the author to emphasize the Jewish condemnation.

May I suggest a book to help:

Though I don’t agree with all of his conclusions, J.D. Crossan’s “God and Empire: Jesus Against Rome, Then and Now” has some very good perspectives on Jesus’ teachings in this direction.